San Francisco Chronicle

‘How do you make an icon more iconic?’: What’s next for S.F.’s Transamerica Pyramid after 50 years

John King , Nov 22, 2022

Even before it opened in November of 1972, the Transamerica Pyramid offered a perspective on San Francisco unlike any other — not just for the outward view, but also to gauge how the city is seen by itself and others.

As the 853-foot-tall tower at the corner of Montgomery Street and Columbus Avenue turns 50, that perspective is as revealing as ever.

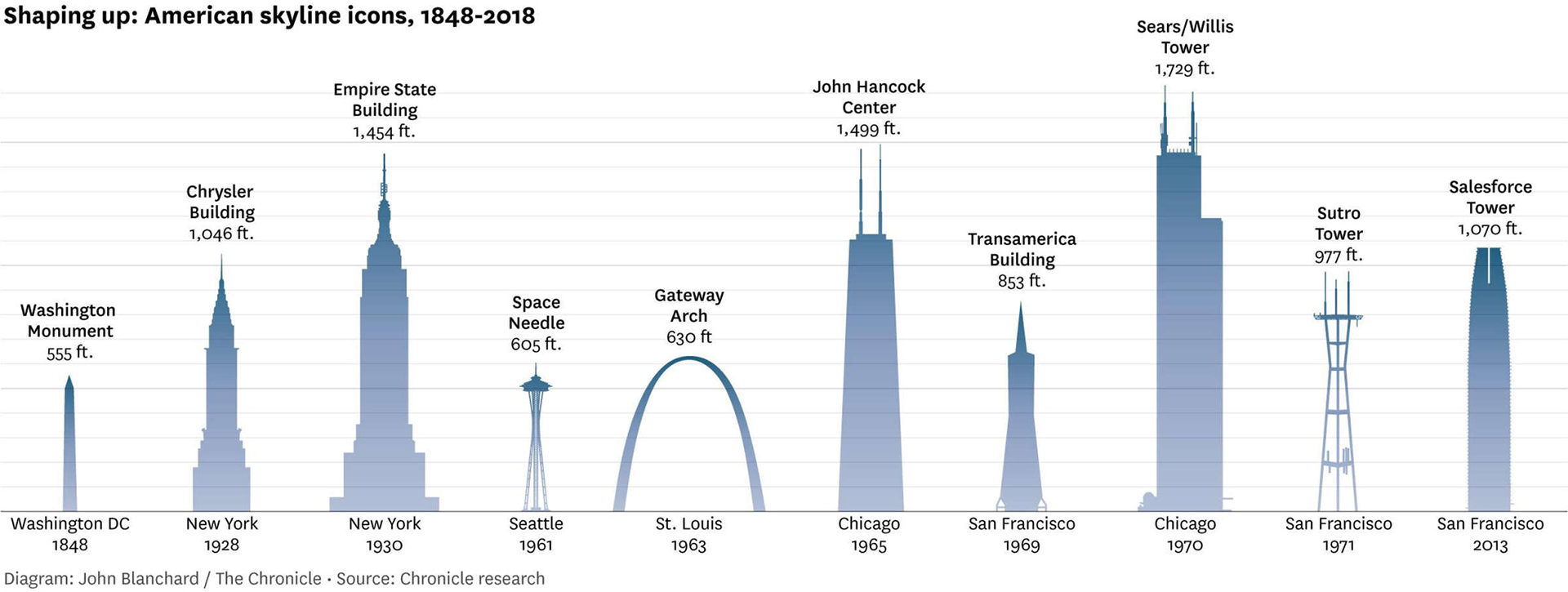

Though no longer the tallest building on the skyline, the tapered concrete shaft rivals the Golden Gate Bridge and cable cars as built icons of San Francisco. The futuristic architecture that angered critics when the proposal was unveiled in 1969 now stands as a reassuring marker for Bay Area residents trying to make sense of the changes around them.

Top: The Transamerica Pyramid peeks out through a fog bank during an evening in June 2014.

Middle: A pedestrian crosses the street with the Transamerica Pyramid in the distance.

Bottom: The Transamerica Pyramid seen reflected in the One Maritime Plaza building from Merchant Street.

Simply put, the Transamerica Pyramid still matters.

“Everyone who moved here or was born after it was built sees it as part of the landscape,” said Christine Madrid French, a historian of modern architecture and author. “There’s a lot of power in that.”

The visual prominence is due in part to zoning that was imposed even before the Pyramid opened, lowering heights north and west of the Financial District so that neighborhoods like Jackson Square and North Beach needn’t fear the spread of attention-getting towers. That zoning in turn cleared the way for tall buildings to spread south of Market Street — such as skyline-topping Salesforce Tower, which opened in 2018 and rises 1,070 feet.

The elongated skyline also signals San Francisco’s southward shift in terms of economics and culture, away from the older high-rises along Montgomery Street or the onetime bohemian enclave of Telegraph Hill. Happening new restaurants are in the Mission, not Union Square.

But if the Transamerica Pyramid marks the spot of where “The City” once was focused, it isn’t some relic that today’s city has left behind.

You see the 48-story apparition with the abstract ears in unexpected places, such as miniature golf courses in Mission Bay and Ghirardelli Square. It’s a fixture on postcards and refrigerator magnets. There’s a folk art version adorning a house on Linden Street in Hayes Valley. Hollywood casts it in such pop extravaganzas as 2020’s “Sonic the Hedgehog.”

Top: Artist Cara Vida stands in her doorway on Linden Alley, which includes artwork depicting the Transamerica Pyramid. The art of the pyramid was first created by her friend Tornado, a woman Vida knew only by that moniker who lived a punk rock lifestyle and died several years ago.

Middle: Dylan Carter, 8, and Maddie Kokoszka, 10, play the 10th hole at Stagecoach Greens mini golf, which features a Transamerica Pyramid boxing with Salesforce Tower.

Bottom: Snow globes found at Wharf Outdoors in Fisherman’s Wharf include a prominent Transamerica Pyramid.

The structure itself is now undergoing a $250 million renovation that won’t change the exterior, which is old enough to be on the National Register of Historic Places. Ultra-lux amenities inside will include a top-floor cocktail lounge restricted to office tenants and their guests. The initiation fees will start at $15,000 for a private club on three lower levels; San Francisco is being added to club locations in New York and Milan because of our “internationally relevant and culturally vibrant” character, the club’s founder told The Chronicle earlier this year.

If anything, the Transamerica Pyramid’s outlier setting at the half-century point adds to its cultural relevance. Being rooted but slightly remote aligns with San Francisco’s image as a city that straddles the future and past, where finding what’s cool requires a bit of effort.

“Architecture imprints itself on our cultural memory,” French said. “It’s definitely a global symbol of the city as a whole.”

The structure conceivedby Los Angeles architect William Pereira for Transamerica Corp. remains striking in the air — 48 stories of continually receding floors topped by a 212-foot cone screened in metal louvers that allow air to pass through. Protruding concrete shafts on the east and west hold elevators and the tower’s mechanical vents. It’s the antithesis of the glass towers now in vogue, and bottom-heavy in a way that seems reassuring in earthquake country.

But the pointed shaft is most startling on the ground.

A concrete thicket of diagonal stilts climbs four stories to form the base for the tower above. There’s no effort to find architectural kinship with its neighbors such as the two- and three-story buildings of Jackson Square directly to the north across Washington Street, where the oldest landmarks date back to the 1850s.

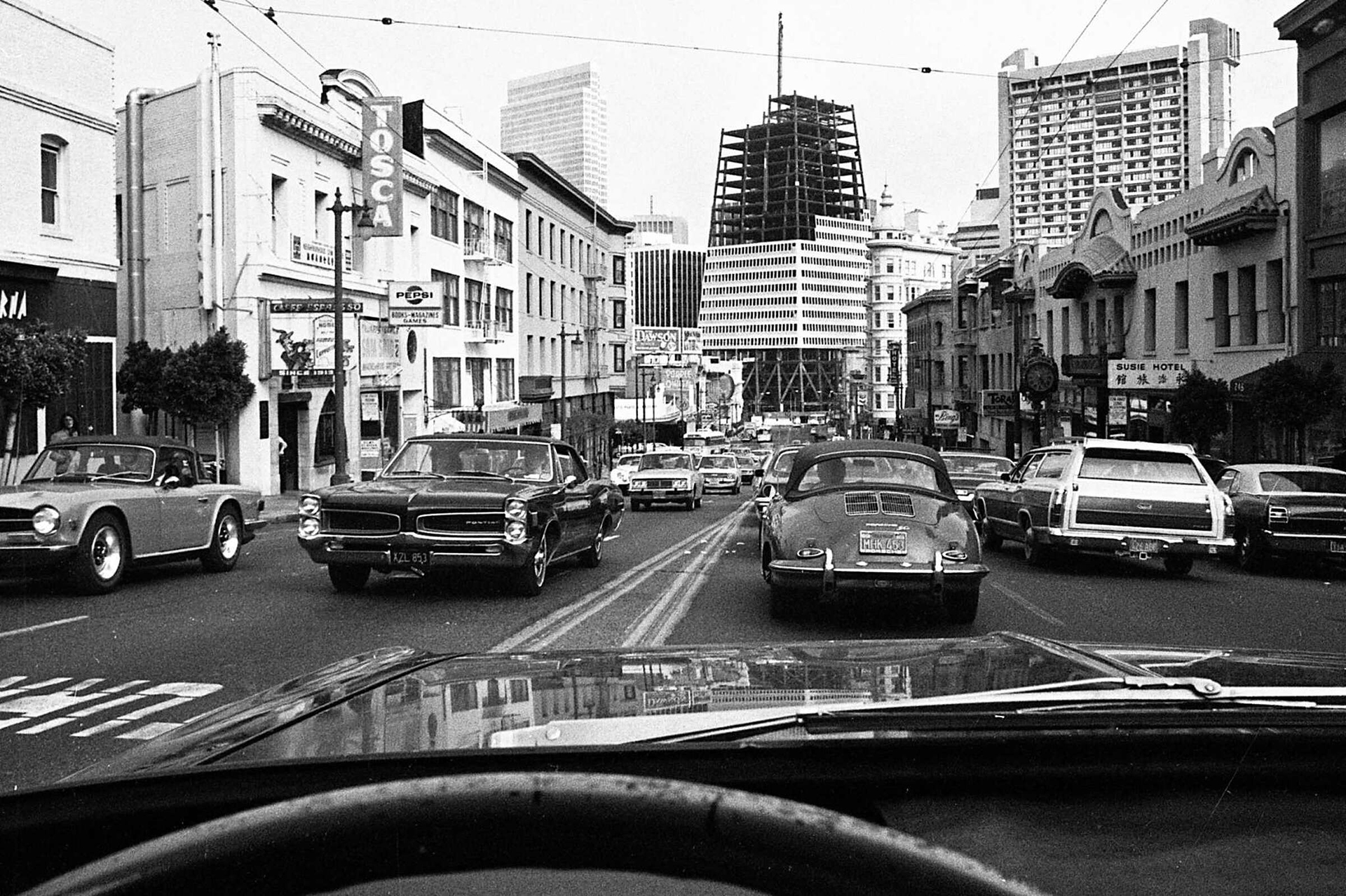

That contrast of short and tall, atmospheric brick and unabashed futurism, is part of what infuriated opponents when the proposal was unveiled in 1969. As Mayor Joe Alioto beamed, Transamerica President John Beckett proudly likened Pereira’s design to “a piece of sculpture.”

Art Frisch / The Chronicle 1969

Art Frisch / The Chronicle 1970

Joe Rosenthal / The Chronicle 1971

Top: San Francisco Mayor Joe Alioto and businessman John R. Beckett display the model for the original 1,000-foot Transamerica Pyramid in 1969. The finished Pyramid was almost 250 feet shorter.

Middle: Construction progresses at the Transamerica Pyramid in 1970.

Bottom: The partially built frame of the Transamerica Pyramid in 1971.

That’s not an overstatement: When Beckett interviewed Pereira, the architect showed conceptual schemes likened to such emphatic forms as an arrow, an oval and a pinwheel. Sixth in the progression of possibilities was a steep triangle — a concept that Pereira originally had pitched to a corporation in New York that instead chose another architect.

This backstory didn’t sit well with people who loathed what they saw as the “Manhattanization” of San Francisco, fearing that their idiosyncratic city would be overrun by corporate slabs. The phrase was popularized by Alvin Duskin, a city native who gathered enough petitions to place an initiative on the ballot in 1971 that would ban new buildings more than six stories tall; the Bay Guardian, an alternative weekly, supported the long-shot bid with “The Ultimate Highrise,” a book that featured a cartoon mocking the Pyramid on the cover.

Nor were complaints confined to the Bay Area. The Washington Post’s architecture critic recoiled from “architect William Pereira’s stuck-up bayonet.” Progressive Architecture magazine likened the potential impact on San Francisco of the sky-scraping shaft to “destroying the Grand Canyon.”

All of which was to no avail.

The Board of Supervisors voted 9-1 to approve the tower despite being told by Allan Temko, who later won a Pulitzer Prize as The Chronicle’s architecture critic, that the design reeked of “plutocratic arrogance.” Construction workers started clearing the site in December of 1969. On Nov. 27, 1972, retail tenant Crocker Bank held a public open house. The deed was done.

The Transamerica Pyramid, as seen from Columbus Avenue, begins taking shape in 1971. Clem Albers / The Chronicle 1971

Skyline battles continued through the decade, but the notion of Pyramid as pariah soon faded. The New York Times’ architecture critic in 1977 called it “the one brightening element” in central San Francisco’s “deadened mass of boxes.” Tourists seeking postcard alternatives to the Golden Gate Bridge or Lombard Street had something new to send friends at home.

“It always sold well,” recalled Jack Hughes, who worked at Smith Novelty Co. selling postcards and other tourist paraphernalia from 1979 until 2020, when he retired from the Daly City-based firm.

Especially popular? A card with the view down Columbus Avenue, the Pyramid rearing up behind the ornate Sentinel Building from 1906.

“People liked the juxtaposition,” Hughes said. “We had a fairly generic skyline until the Pyramid and then, you knew, that’s San Francisco.”

Stand where Columbus meetsMontgomery and Washington streets today, and a solid wooden fence greets your eyes along the street. Some sections bear the cryptic inscription “PEREIRA + FOSTER + SHVO.”

Pereira is obvious, the architect who, when asked later by a reporter what he’d do if he could turn back the clock, replied, “I’d make it taller by 200 feet.”

Foster is Foster + Partners, the architecture firm founded by Norman Foster that now has 16 offices on five continents, with a portfolio including Apple’s headquarters in Cupertino.

Shvo is Michael Shvo, the New York developer who in 2020 paid $650 million for the Pyramid and the block’s two other (much) lower buildings from Aegon, the insurance giant that purchased Transamerica Corp. in 1999.

Current plans call for the most thorough refurbishment the Pyramid has received since it opened: The skin’s quartz aggregate will be blasted clean. The peak will have LED lighting installed behind the metal louvers to allow different hues at different times, updating a feature of the original tower. All common areas inside will be redone.

On the ground, the aim is to blur the lines between public sidewalks and private plaza. Small deciduous trees will be planted within the concrete thicket. Redwood Park will be enlarged by 1,000 square feet while being returned to landscape architect Anthony Guzzardo’s original design.

A pedestrian alley from Sansome Street will be adorned with cherry trees and shop spaces. Along its north side, a nine-story office building will grow to 15 stories, with a sleek contemporary and terraced addition.

“We want a vibrant energy at the base of the building,” Shvo, whose financial partner is Deutsche Finance America, said in a telephone interview this month. “To bring a human element to a beautiful concrete structure, with a park in the middle of the city.”

Later in the interview, Shvo succinctly framed the challenge as he sees it.

“How do you make an icon more iconic?”

Top: The Transamerica Pyramid on a night in September.

Middle: A view of the Transamerica Pyramid from the ground.

Bottom: The Transamerica Pyramid is seen beyond the artwork “The Language of the Birds” in North Beach.

For all its architectural power and visual recognition, the Transamerica Pyramid comes up short in one key way. It says little about San Francisco as a whole.

That’s different than City Lights bookstore on Columbus Avenue, which embodies the boundary-pushing cultural ferments of the city as surely as when poet-owner Lawrence Ferlinghetti published Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” in 1956. Or the Ferry Building, with its distinctive clock tower that has witnessed the Embarcadero’s transition from entry point and working port to lifestyle zone, Pier 39 at one end and the Giants’ Oracle Park at the other.

Transamerica Pyramid instead radiates an aura that’s brawny yet nonchalant, aloof yet enduring, showing the extent to which something seemingly taboo — a modern shaft amid historic masonry, a spike on a then-uniform skyline — can be embraced by society at large.

Top: An advanced apprentice works with a younger student at Yau Kung Moon Tak Fung Gwoon on Waverly Place with the Transamerica Pyramid visible out the fourth-floor window in San Francisco in October.

Middle: The Transamerica Pyramid peeks out above the basketball courts at Willie “Woo Woo” Wong Playground as children play.

Bottom: Visitors to the Salesforce Ohana Floor look out northward to see the Financial District and North Beach, including the Transamerica Pyramid.

This iconic aspect is almost certain to endure in coming decades, just as that International Orange bridge still shines in the popular imagination. The open question is whether Pereira’s Pyramid will take on additional layers, and reflect deeper aspects of urban life.

The plans for the block’s ground level offer a start, suggesting a public realm that truly feels public. Part of the city’s daily life, a spot embraced by San Franciscans and visitors as common ground.

If this happens, the Transamerica Pyramid might help to redefine 21st century urbanism. Which would make it symbolic of something larger after all — because that’s also the challenge facing San Francisco itself.

Reporting by John King. Editing by Robert Morast. Visuals by Carlos Avila Gonzalez. Visuals Editing by Nicole Frugé and Guy Wathen. Graphics by John Blanchard. Graphics Editing by Hilary Fung. Design and Development by Stephanie Zhu and Alex K. Fong. Icons by Font Awesome / CC BY.